Our firm focuses on digging deeply into the performance of solar systems and faults that can emerge. We have a saying here that “defects are a jewel to be treasured”. What we mean by this is a defect properly investigated tells you a lot about improvements you might need to make to your processes and systems. If you ignore or sweep that defect under the rug or try to assign blame you miss that opportunity. There is a lot of timeless wisdom from the Tao Te Ching when it says “Failure is an opportunity. If you blame someone else, there is no end to the blame”.

The The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization by author Peter Senge describes systems thinking as the fifth and most important discipline. I was really impressed by his writing when completing my MBA and have tried to incorporate systems thinking into my work since then. I am going to suggest if we are going to successfully transition to a clean energy future we need to adopt systems thinking and can’t rely strictly on specialists.

So I’ll give you a real world example of why we need system thinking and how relying only on specialists can lead to unexpected problems.

We were approached by a potential customer with a number of systems to see if we could help them with monitoring and finding underperformance that they suspected was present but undetected in some of their systems. We were able to help with that but that is a story for another article. We also knew they had an additional combination PV and EV charging carport and we were interested in that for research purposes. However, for a variety of reasons arising during construction, that system lacked an internet connection for remote monitoring. So our contact went onsite to see what was possible and noticed that the inverter had an error code, wasn’t producing and probably hadn’t been for quite some time.

Now I’m a software guy and have never installed a solar system, but I do know how to debug system problems. So I stopped by and looked at the system and the error code. We’ve tried to learn as much as we can about solar systems and their problems over the last few years so I wasn’t going in completely blind.

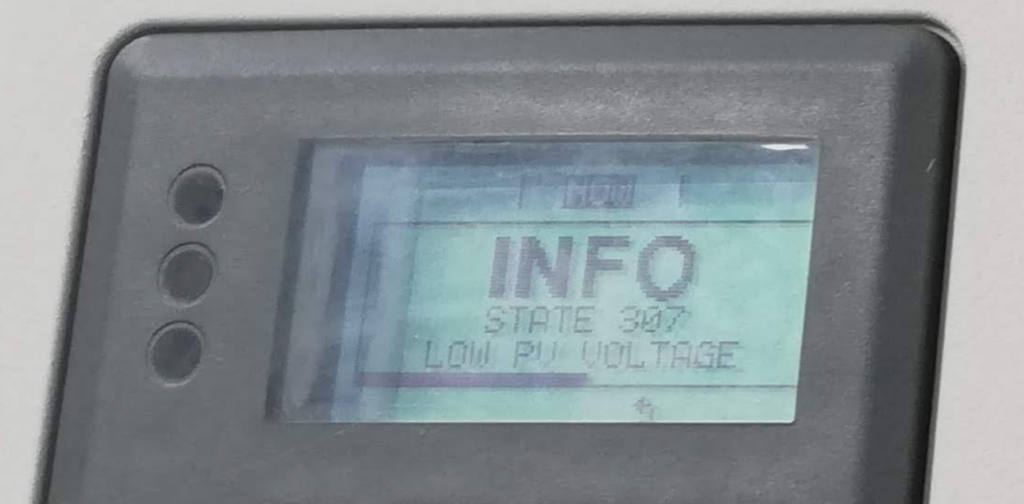

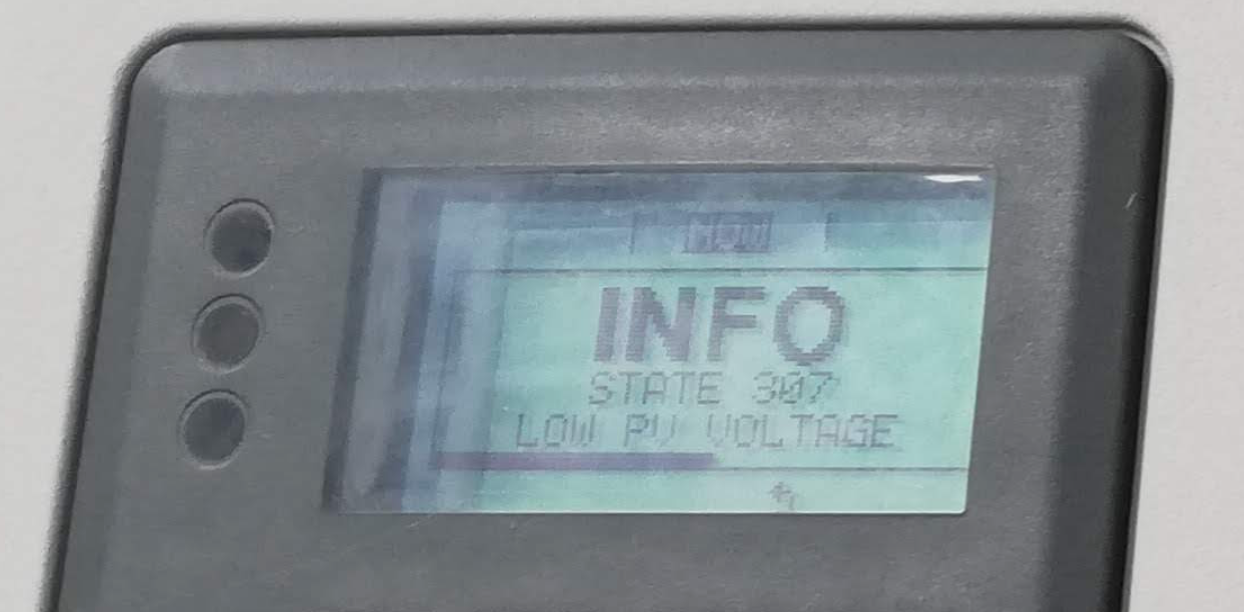

I took some pictures, did some research and developed a theory. The picture you see was of the inverter screen saying “Low PV Voltage” even though the sun was shining. H’mmm I thought let’s assume there are multiple strings, I find it highly unlikely that all are failing at this point.

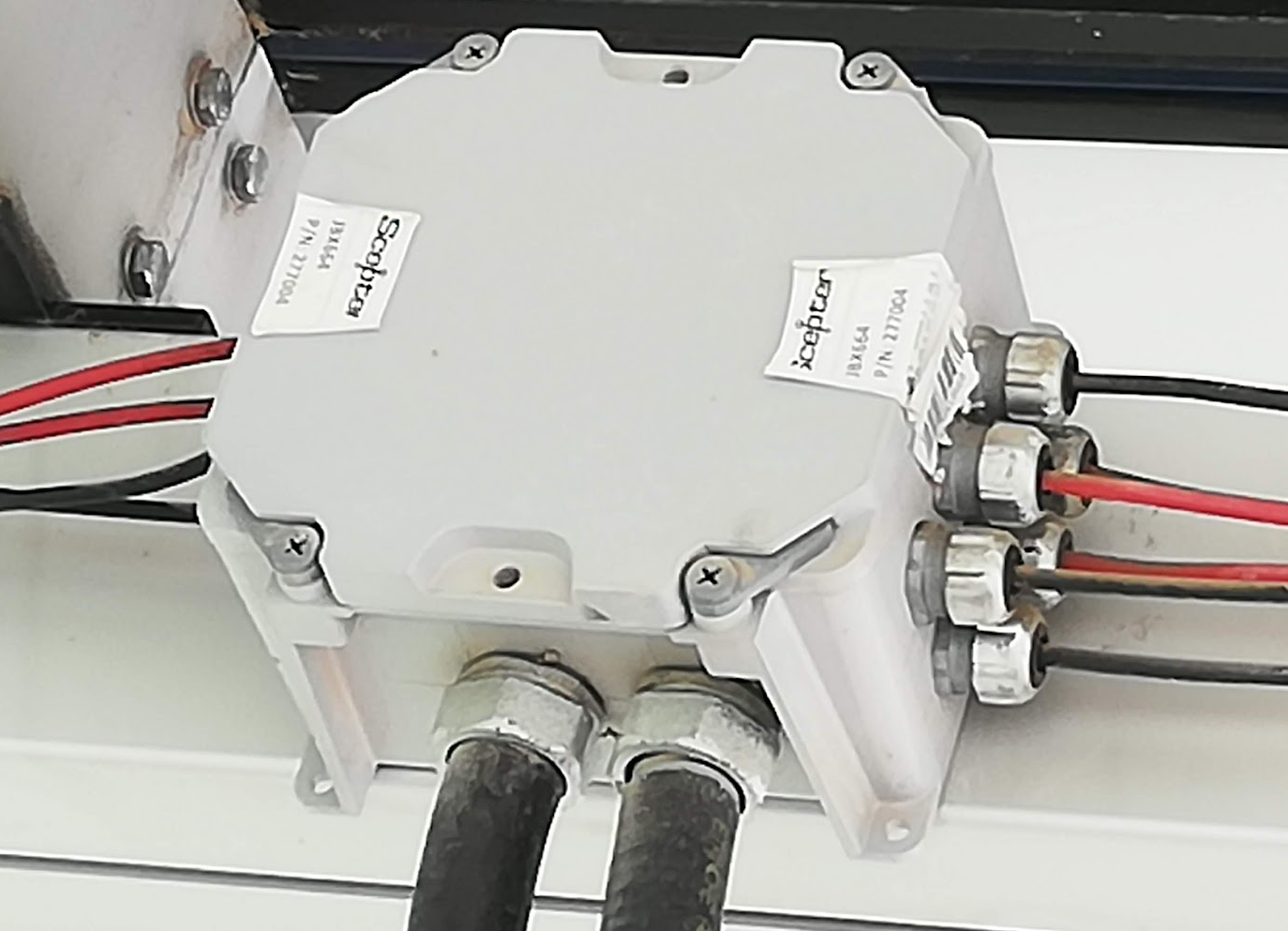

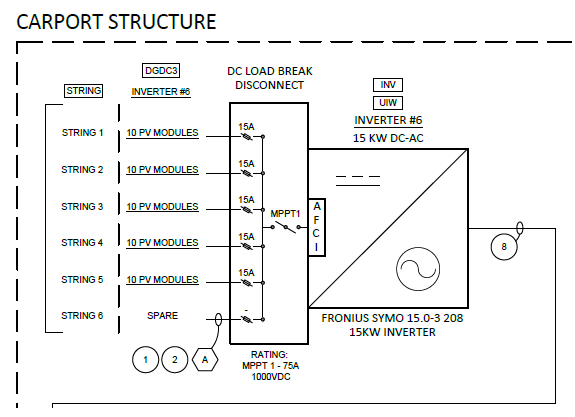

So I looked at the layout of the system and the strings, counted solar panels and looked at the combiner box shown here. I could see there were 50 panels, arranged into 5 strings of ten panels.

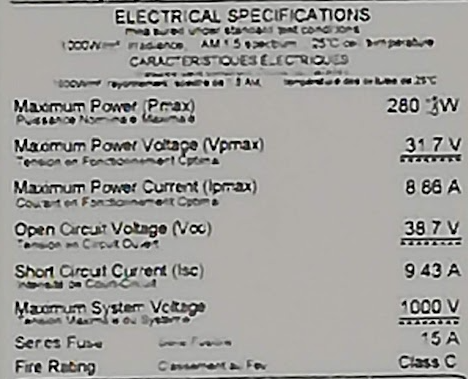

So what about the panels themselves? Since it was a carport I could zoom in with my cellphone to take a picture of the rating sticker on the back of the panels. The important value on the sticker is the Maximum power voltage of 31.7Volts at 25C. So let’s do some math, with 10 panels under optimal conditions the string total is 317 volts matching the OESC labelling on the inverter.

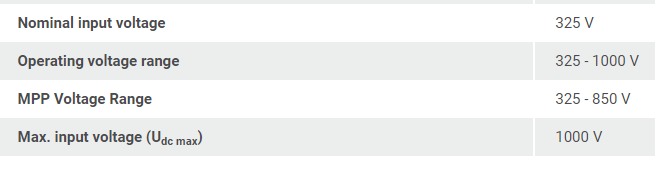

But what about the inverter input voltage range I thought, given the error code? Using the inverter model number here is what I found. The minimum operating voltage is in fact 325 and 600 is a better number to aim for. So with less than an hour’s effort and a little generalist knowledge, I seemed to an answer to the problem. I then talked to various specialists who then confirmed the theory and the solution being reconfiguration with fewer strings taking advantage of the multiple MPPTs on that particular inverter.

What went wrong and who is to “blame” is one way of approaching this defect. However, we then was miss the jewel to be treasured because it was a whole combination of factors that lead to this problem. Let me describe the series of events that left me standing in a parking lot staring at that inverter error code.

The first was relying too heavily on siloed specialists and not having experienced active monitoring in place. The system was installed almost three years ago and probably has been producing very little power only under ideal conditions since then. If active remote monitoring was in place, the problem would have been caught much earlier. The issue with PV systems is there often isn’t a flashing red light saying help me I’m broken. In this case we were lucky that you could see the problem looking at an easily accessible inverter, wiring and panels in a public parking lot. Most of the time that isn’t the case, hence the need for remote monitoring, engineering diagrams etc. This is also where I chuckle with software firms claiming they can easily find faults in solar systems relying on the wonders of AI and machine learning. Good luck if a whole bunch of solar specialists had missed this problem.

So why wasn’t remote monitoring in place? The original plan was to locate the carport closer to the building and connect via Wi-Fi. However, due to shading concerns it got moved farther away and where Wi-fi didn’t reach. At that point it was too costly to run a physical ethernet cable and a cell modem wasn’t included in the original system design, so no remote monitoring was put in place.

In addition, there was a decision to swap the type of inverter used for consistency across the sites and so a single monitoring platform could be used. That is a very consistent need we see in the market and hence why people use us because we integrate with a variety of systems in a common platform. However, that switch in inverter had an unintended impact because undoubtedly the original inverter had a lower input voltage and probably a single MPPT because this is a popular carport vendor.

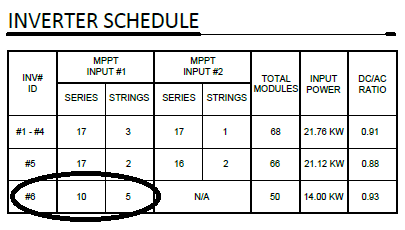

You can see how much shorter the strings were for the carport relative to the other inverters on the building itself in this inverter schedule. The intent was probably not to use multiple MPPTs on the carport because of the original inverter. However, the installed inverter like the other inverters supports multiple MPPT inputs so could accommodate 50 panels.

So this started as a design problem which happens, but how did it get through the commissioning process without the problem being discovered? For me that’s where it gets interesting. I was able to access the AC testing report and saw when it was performed.

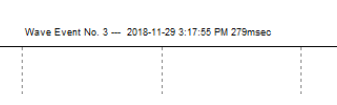

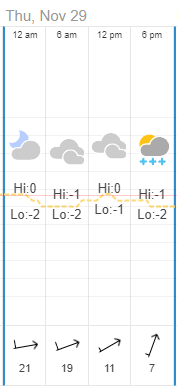

The AC testing was performed late in November in the afternoon and here was the weather for that day. It was a slightly cloudy cold afternoon with the temperature hovering near 0C, absolutely perfect for the panels because they were well below 25C and they perform better at lower temperatures. The AC report showed it was probably producing at 10% of rated capacity because of the time of day and clouds but it was producing at that point so could pass the test because the total string voltage probably reached 325 volts or the inverter could accept slightly less than that to start producing.

As you can see from this story there really wasn’t anyone to “blame”. Sure various specialists had the ability to have done something differently and the problem would have been caught sooner, but they basically were just following standard practices and yet the system wasn’t producing for almost three years!

In other situations we’ve seen, I would say that I would have expected the problems to have been caught earlier. Instead, I selected this example because as you can see there are a whole variety of factors and no clear mistakes made.

In closing if you require some systems thinking to your solar system problems, let us know and perhaps we can help. Hopefully this article also gets you thinking about how we can apply system thinking in other ways as we transition to a clean energy future.